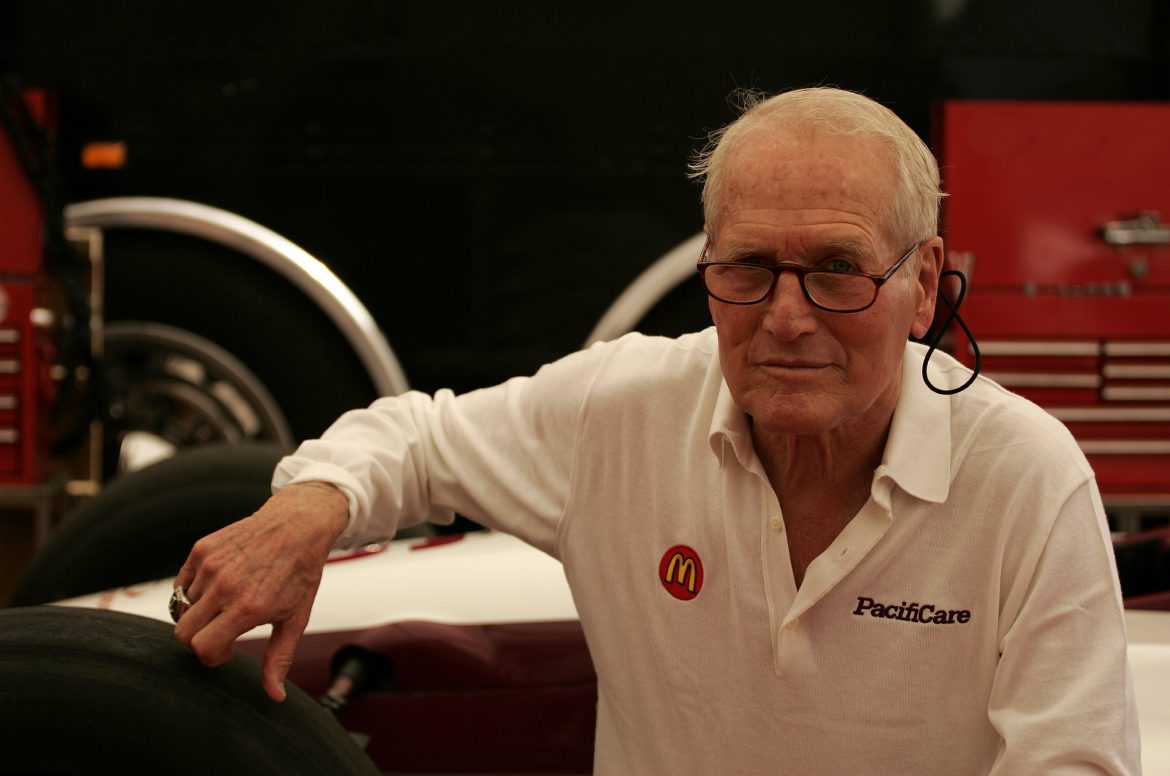

We’ve obviously gotten it all wrong over the years, thinking Paul Newman was an actor moonlighting as a racer. For more than three decades it’s been the other way around.

Newman doesn’t have to attend Champ Car races week in and week out, even as the co-owner of four-time series champion Newman/Haas Racing. After all, how often do other ‘celebrity’ team owners show up – say, David Letterman?

No, Newman wants to spend his time at the race track. Or maybe he needs to be there, in a way that many readers of this magazine can surely relate to.

“Paul’s passion is real,” reckons Mario Andretti, the man whom Newman/Haas Racing was built around back in 1983. “This isn’t some Hollywood rich boy out there posing. The guy just loves cars and racing.”

He loves Champ Car racing in particular, having been introduced to the sport when he filmed ‘Winning’ in 1969. Newman played Frank Capua, a down on luck racer who bounces back to win the Indianapolis 500. Three years later – at age 47 – he launched his own successful driving career (see sidebar) and he’s been actively involved as a team owner in SCCA Can-Am and Champ Cars since 1979.

Newman didn’t get into racing because of the money; if money mattered to him, he wouldn’t have donated the $150 million in profits his eponymous food products have generated since 1982 to charity.

“I think if you have a passion for one thing it bleeds back into a lot of other things,” Newman remarks. “In my younger and medium years I was passionate about acting and as that kind of became tiresome it was replaced by racing. Then some of that bled back into my acting and my family.”

It’s ironic that a movie based around the Indy 500 sparked Newman’s longterm interest in racing because in the 1990s, he developed deep philosophical differences with the management of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway under Tony George. In fact, Newman has emerged as Champ Car’s most ardent and visible supporter and he is only too happy to express his opinions about the state of American open-wheel racing circa 2004.

When we spoke in Toronto, it was in the midst of the clandestine meetings between Champ Car and the Indy Racing League that ultimately failed to unify the two open-wheel series. Like many observers, Newman believes the open-wheel war was unnecessary in the first place and harmful to the sport in the long run.

“I think stock car racing was in the ascendancy but we certainly made it easy for them,” he begins. “We made a lot of mistakes. We did not have a support series that brought in new stars directly, as they were smart enough to do in motion pictures, and there was bickering among the owners.

“Still, we would have been much stronger and much healthier and would be having a lot more fun if that schism hadn’t occurred. And there was no reason for it. It was just stupid. As time continues, it makes it even more stupid. I think if it was reunified it would gather strength. If it’s not reunified, (Champ Car) will gather more strength than the IRL will.”

Newman bases that belief on what he sees and hears. What he sees at Champ Car events are lots and lots of dedicated fans – and he listens to them when they seek him out.

“The tradition of road racing in this country runs deep, it runs powerfully and it runs loyally,” he notes. “With all the crap and the backbiting that the fans have heard, the people that have remained the most loyal, the most patient and the most forgiving are those people sitting out in the stands. They are the ones who are really to be applauded – and in the final analysis, those are the ones that we should pay the most attention to and should honor. It’s extraordinary. I mean, Jesus! They should have divorced us a long time ago.”

Yet Newman knows from personal experience that Champ Car racing isn’t a tough sell if the right people are doing it. He’s reticent to promote his movies, but he will happily talk to anyone about his racing team. In April, he plugged the Champ Car series for an hour on “Larry King Live,” then enticed Paul and Heather McCartney and Tom Cruise to the Long Beach Grand Prix a few days later.

Newman believes in the Champ Car product strongly enough that he put his own good name on the line to convince PacifiCare and McDonald’s to spend millions of sponsorship dollars in what many portray as a dying series. But he flat out doesn’t see any appeal in the IRL.

“I would much rather go to a race with 60,000 or 70,000 people in the stands and watch a good road race than to stand around where there are more people in the pits than there are in the stands,” he says. “A combination of road racing, street racing and a few ovals is the formula that really excites me. I think a championship with all those disciplines involved is a much more complicated and worthwhile championship.”

He has a high opinion of Champ Car’s new owners and their plans for the future. “Don’t forget, there was a tremendous amount of rear-guard action that this management had to put up with at the beginning,” he points out. “They weren’t allowed to function on the future because they were so busy fighting off attacks, whether it was the court case or someone telling their promoters that next year they would be the first in line for the next IRL race…although why anybody would want an IRL race, I don’t know.

“Now that they have gotten past this rear-guard action and all this sniping and other stuff floating about, I think they’ll be able to start making some real progress. They have had a very, very difficult year and they haven’t really been able to hone in on their focus. But our product is going to get better and the television coverage is going to get better.”

Some might suggest that if Newman has such clout and interest in the sport, why doesn’t he follow Roger Penske’s lead and attempt to broker peace between Champ Car and the IRL? Newman knows that there is only one person who can make that happen.

“A rapproachment?” he asks. “That’s up to Mr. George. Everybody is willing to talk except Tony George. That’s clear and it’s public. It’s not as though I’m throwing something out on the table that is a bad hand.”

He pauses before continuing. “Everybody is willing to talk but nobody is willing to join with Tony George as the chief operating officer,” he eventually says. “That would be like sticking a rifle in your mouth. We have made mistakes, but we didn’t make as many mistakes as he did. But as I say, I think we have a better chance of getting stronger than he does, and this is certainly a hell of a lot more fun.”

After more than twenty years in Champ Cars, it saddens Newman that many of his top competitors bailed on the series at a time when it needed them most. “The thing that I personally regret is that it was great fun and a great challenge to beat and to race against Penske and Ganassi and Rahal and all those other guys,” he reflects. “I miss them, and I miss the competition that racing brought. If they’re smart, they’ll come back.”

In the meantime, it is his own team that is the latest to be linked to a big-money move to the IRL. Newman was not one hundred percent in favor of Newman/Haas running a car for Bruno Junqueira in this year’s Indianapolis 500, and insiders believe that Carl Haas and his wife Bernie have signed a multi-year deal with Honda to compete full-time in the IndyCar Series. A split effort between Champ Car and IRL is the most likely outcome, and Newman chooses his words carefully when addressing the future of Newman/Haas Racing.

“We are trying to keep the team together for a lot of reasons,” he says. “It’s a partnership that has lasted for a long time and we have people who have been working for us for 20 years. We don’t want to split the team up and split the loyalties. But whether we will be able to keep the team together, I don’t really know yet. That’s our first objective.”

In truth, Newman needs to think about his own interests as well. He’s trim, fit and healthy, but he’s still 79 years old and knows that time is a finite resource. And he still has an acting career with as much work as he desires, most recently starring in a production of “Trumbo” at the Westport Country Playhouse near his Connecticut home. He also has a TV movie in post-production and a voice-over role in the upcoming animated motion picture ‘Cars.’

“My wife has been the artistic director at the Playhouse and her duties will be over there at the end of next year,” Newman relates. “It has occupied a huge amount of her time and we haven’t been able to spend a lot of time together. That’s gotta change, because that’s no fun for either one of us. But she has been very patient about my racing, I must say. She comes to them. She brings the grandkids and she gets out there and yells louder than anybody.”

Five years ago, Newman’s acting and racing careers did merge in a unique way when he agreed to slip back into the character of Frank Capua for a Champ Car magazine interview. Naturally, he nailed it, and many of his observations were spoken with the wisdom of a lifelong racer. Champ Car and the IRL might do well to heed Capua’s words as they head their separate ways into the future.

“I don’t see where the sport is going,” said the fictional racer. “Now the ‘show’ is everything and racing had better be careful not to lose sight of what this sport is really about – racing. All I read about is slowing down the cars, slowing down the tracks. I don’t know if you can slow down progress. The only thing I can see getting quicker is how fast the money leaves your wallet when you get to a race. That seems to be the same for everybody – tracks, owners and fans.”

Back in the present, Paul Newman has a race to watch, a street race before more than 72,000 fans that his driver Sebastien Bourdais would go on to win. He cracks a smile as he dons his sunglasses.

“The last statement I would like to make is this,” he says mischievously, before heading out to the pits. “If Tony George were 200 million dollars less rich, this whole thing might come together very quickly.”

-30-

Paul Newman admits that filming ‘Winning’ got him hooked on racing.

He drove an Eagle Champ Car powered by a turbocharged Offenhauser engine in the movie, albeit not at racing speeds.

“I had a great deal of fun filming the film, but I never really had a chance to stretch my legs out and find out what I could do in a car,” he says. “It actually took me three years of rearranging my schedule before I could find time to get my license and everything. After that, I never did a film between April and September or October. Racing was all I did.”

He had the good fortune of living near Bob Sharp, who dominated SCCA racing in a series of Datsuns in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. “He had a really classy, sophisticated operation and so that’s how I started, driving a little four-cylinder Datsun,” Newman recalls. “I just worked my way up. There was no point in racing unless I really took it seriously, so that’s what I did. I thought there was a faint possibility that I might get good at it one day.”

Despite getting a late start as a racer, Newman quickly displayed a smooth unhurried style that helped him win four SCCA national championships. By the late ‘70s, he was racing professionally, finishing fifth in the 1977 Daytona 24 Hours and second in the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1979. Newman is also a two-time winner in the SCCA’s Trans-Am series, including a victory at his home track of Lime Rock Park in 1986 when he was 61 years old.

“Racing really grabbed hold of me,” he now admits. “It was the only thing I ever had any grace in.”

Newman cut back his racing schedule in the late ‘80s, but he didn’t stop winning. He was 70 years and 10 days old when he co-drove the winning GTS entry in the 1995 Daytona 24 Hours, and he again competed in the Florida endurance classic this year at the age of 79. Last year he finished fifth in a one-off Trans-Am start at Lime Rock and his most recent outing came in June when he drove the #79 “Happy Hands Massage” Corvette to a xth place finish in the ____ series race at _____.

“I had no idea I would become as passionate about racing as I did and it has given me a tremendous amount of pleasure and a lot of confidence,” Newman notes. “I didn’t start until I was 47, but I was a pretty good driver for about five years.”

-30-